Category Archives: Uncategorized

Inauguration of the Offices of the Joint Secretariat (JS)

Peace Forum with Luis Jalandoni and Silvestre Bello III in August 2004

GPH-NDFP Peace Negotiations, Oslo, Norway Feb. 15, 2011

GPH Panel Chair Alexander Padilla, RNG Ambassador Ture Lundh, and NDFP Panel Chair Luis Jalandoni shaking hands before starting the morning session

GPH’s Alexander Padilla (left) and NDFP’s Luis Jalandoni exchange panel credentials during the Opening Ceremonies of the Formal Peace Talks. Oslo, Norway, February 15, 2011

The GPH Panel on the left, the RNG Facilitators at the center and the NDFP Panel on the right. (Photo by Mayet Atienza)

Ministers and ambassadors of the Royal Norwegian Government, Third Party Facilitator to the GPH-NDFP Peace Talks. (Photo by Mayet Atienza)

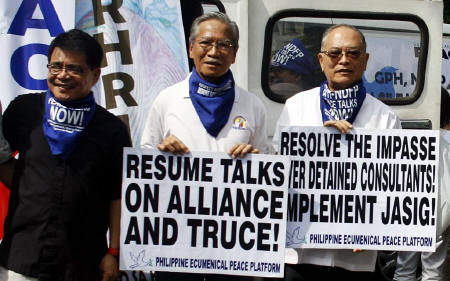

A GATHERING AND CARAVAN FOR PEACE

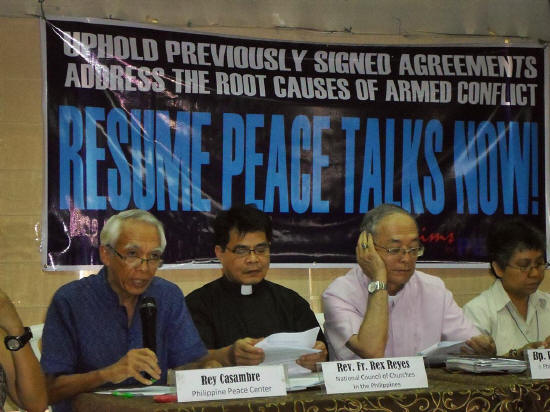

PEACE ADVOCATES CALLING FOR PEACE TALKS RESUMPTION

PHILIPPINE INDEPENDENT CHURCH BATS FOR RESUMPTION OF NDFP-GPH PEACE TALKS

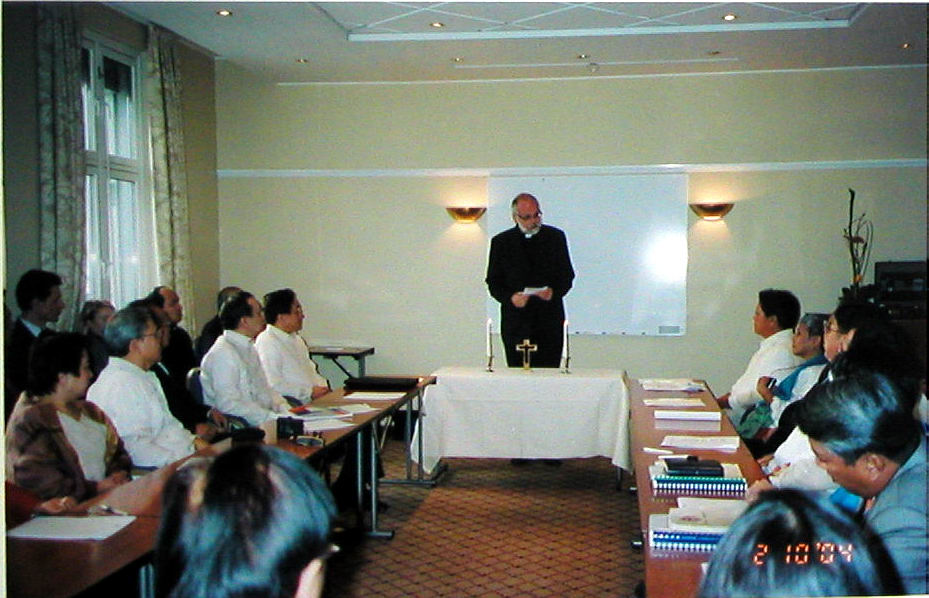

Utrecht – Sept. 18 — Delegates from the Iglesia Filipina Independiente (IFI-Philippine Independent Church) headed by Supreme Bishop Ephraim Fajutagana and members of the NDFP Peace Negotiating Panel met yesterday in NDF Office in Utrecht, The Netherlands to discuss prospects of peace talks with the GRP.

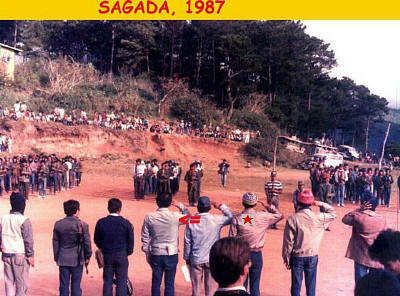

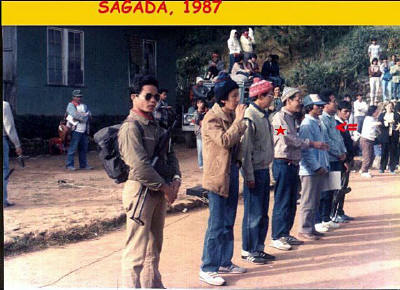

The 1986-97 Peace Negotiations

Peace talks between the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) were first conducted in August-December 1986 under the Aquino administration. After signing a 60-day ceasefire agreement, the GRP showed no more interest in discussing the substantive agenda. The talks collapsed after government troops fired on unarmed peasants demonstrating for land reform near the presidential palace, killing nineteen and injuring hundreds, in January 1987. On March 25, 1987, President Aquino unleashed the sword of war against the New People’s Army (NPA) and the revolutionary movement.

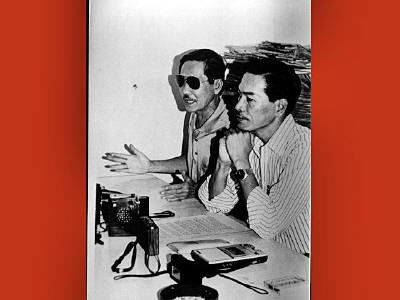

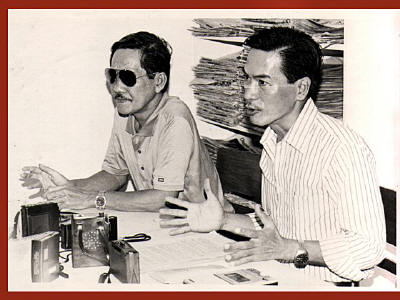

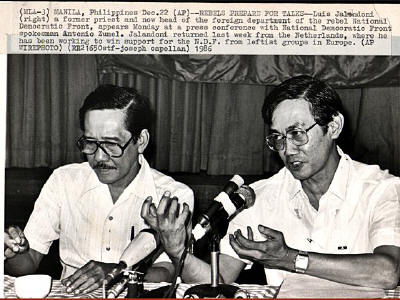

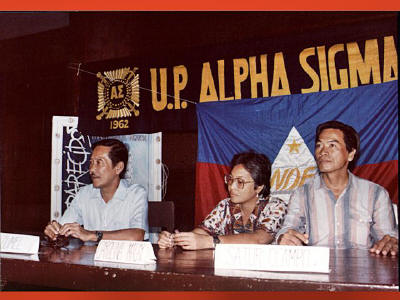

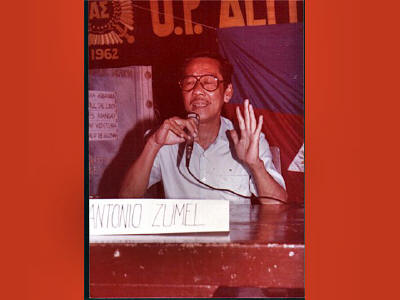

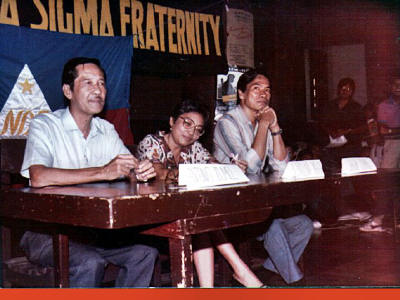

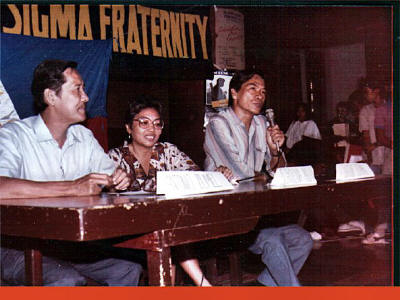

Satur Ocampo and Antonio Zumel in a press conference while still in the underground, Dec. 1986

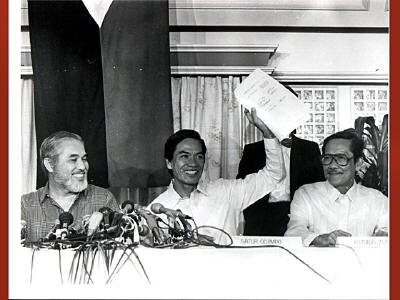

Satur Ocampo and Antonio Zumel at UP Alpha Sigma press conference

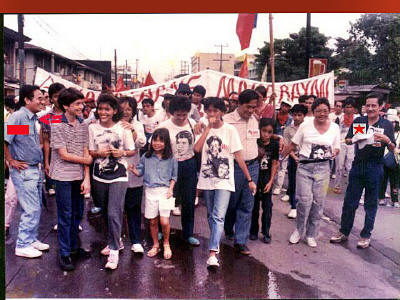

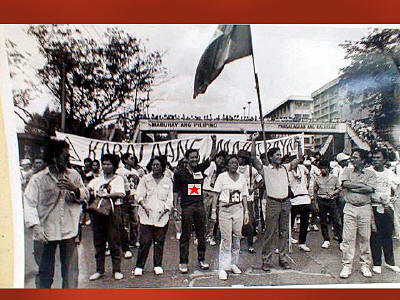

Satur Ocampo and Antonio Zumel in Ka Lando Olalia funeral march

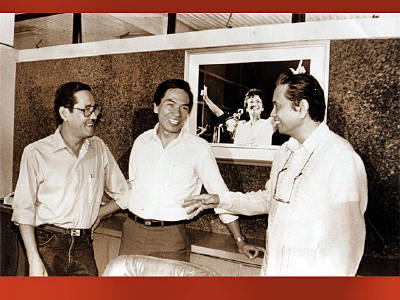

Satur Ocampo and Luis Jalandoni with Sen. Teofisto Guingona, 1986

Dec. 22, 1986 press conference

FIRST GRP-NDFP NEGOTIATING PANEL SIGN PEACE AGREEMENT IN 1986

The NDFP Panel: Satur Ocampo, Antonio Zumel and Carolina Malay The GRP Panel: Ramon Mitra, Jr., Tito Guingona and Jovito Salonga

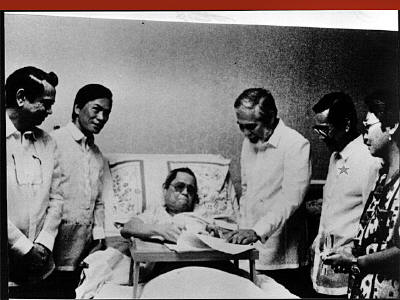

Jose W. Diokno signing the agreement in the hospital

The NDFP Panel with Atty. Romeo T. Capulong and Atty. Arno Sanidad Sen. Nikki Coseteng and Antonio Zumel

Members of the NDFP Negotiating Panel conducted consultations with various units in the field. But the peace negotiations ended abruptly when state security forces fired upon protesting farmers in Mendiola on January 22, 1987, killing several peasants and wounding scores of protesters.

sitemap

The Human Security Act and the Rule of Law Political Repression and the Peace Process

The Forces of Change Must Prevail- Peace Negotiations in the Philippines

CONDEMN AND OPPOSE US PLAN TO BOMB SYRIA AS THE OPENING ACT OF A WAR OF AGGRESSION

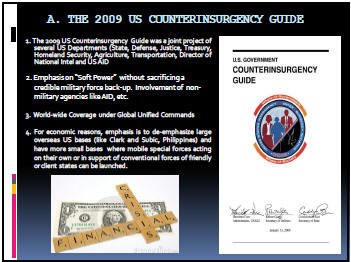

The Role of Overseas US Military Bases, US Special Forces, and the 2009 US Counter-insurgency Guide

‘Security tensions’ in South China Sea and the U.S. arms industry

Joint Agreement on the Ground Rules of the Formal Meetings between the GRP and NDFP Panels

Additional Implementing Rules Pertaining to the Documents of Identification

THE RAMOS PEACE PROGRAM – TOWARDS A GENUINE PEACE OR A MERE PACIFICATION PROGRAM?

GRP-NDFP Peace Talks TOWARD AN AGREEMENT On Human Rights And International Humanitarian Law