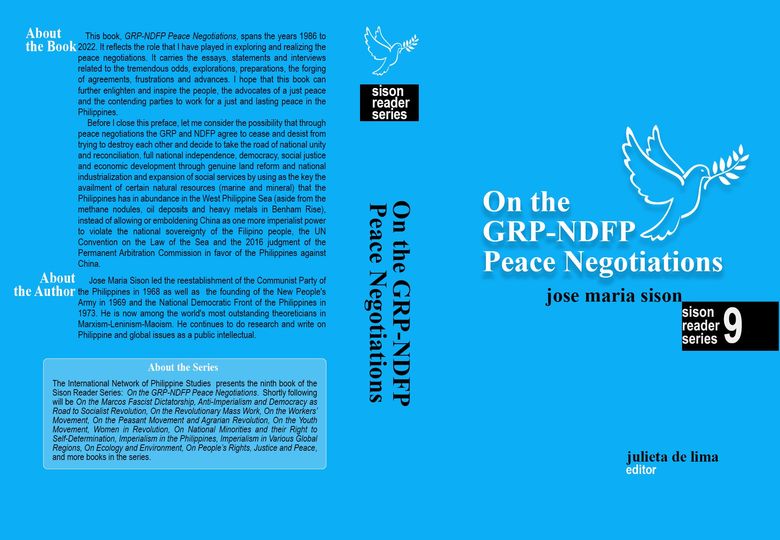

A book review of the Sison Reader Series Book No. 9, On the GRP-NDFP Peace Negotiations by Jose Maria Sison

BY ATTY. LILY CRUZ

Posted on 7/05/2022 from Arkibongbayan

Constant upheaval and irrepressible revolutions have always been a central feature in the Philippines, where the sublimely serene landscapes contrast with the intensity of political conditions amid fraught social structures. A long history of conflict has inevitably led to several peace tables, all intended to address deeply-rooted inequalities, well-seated oppression, and persistent poverty. But beyond reaching an agreement, the greatest question has been whether these agreements can really bring a sustainable peace.

That the world’s longest running insurgency has engaged in peace negotiations for thirty of its fifty years shows that peace, while elusive, is not automatically illusive. Talks between the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) and the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) have been slow but relatively steady. So far, the parties have mutually concurred on framework agreements. With discussions now stalled over substantial reforms and political motivations, and at the dawn of a second Marcos administration, Professor Jose Maria Sison timely reminds us that the very objective of the communist war in the Philippines is ultimately, peace.

Celebrating the golden jubilee of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) a few years back, Prof. Sison called upon the party to intensify the war, and at the same time, advocate for peace. Readers of the book will know that these two faces are not contradictory, but rather, two sides of the same coin.

The ninth book in the Sison Reader Series tackles a wide array of issues, under the all-encompassing theme of “on the GRP-NDFP Peace Negotiations”. Meaningfully, it is bookended by an interview about the 1986 elections, and another about the 2022 elections. This collection of articles and works tracks the history of and lays out the politics, as well as philosophical underpinnings, of the peace movement in the Philippines. Previously, the NDFP had published the booklet introducing “Two Articles on the People’s Struggle for a Just Peace” (2015), as part of the education series of its Human Rights Monitoring Committee. This new book is a broader, more definitive collection of his thoughts relevant to the subject, delving into substance and procedure, as well as general and specific topics.

Very few can talk about this with the gravitas and authority of Prof. Sison, the chief political consultant of the NDFP at present. As the acknowledged founder of the new communist party, which the NDFP represents at the table, he not only has the institutional memory but also the greatest personal influence over a group that has persistently clawed at pretensions of a pacific democracy. Through the years, Prof. Sison has actually emerged as one of the biggest stalwarts of the peace movement, resolutely holding on to pending collective demands and to possible post-conflict unities.

His logic, precision, and consistency, especially when speaking on the root causes of the communist revolution, lends an academic flair that will make the book a reliable reference for all kinds of scholars and students. Three of the longest articles, “History and Circumstances Relevant to the Question of Peace” (1991), “The NDFP Framework in Contrast with the GRP Framework” (1991), and “On the Question of Revolutionary Violence” (1993), give us exquisite, comprehensive narratives of conflict in the Philippines and offer incisive analysis direly lacking in textbook works. The professor in Sison shines through, as he seamlessly shifts through academic perspectives and melds social science theories with practical applications.

At the same time, his use of the active voice and personal pronouns joltingly persuade. Prof. Sison, in true Marxist fashion, dares readers to not only interpret the world, but to change it. His frequent exhortations to arouse, organize, and mobilize creates a cadence as he seemingly directs an orchestra – cadres of the red army, members of mass organizations, supporters of the national democratic movement – towards harmony in work. In recognizing that all persons can play a part in peace-building, Prof. Sison appeals to and educates a general audience. His political and polemical writings certainly deserve its space alongside foremost critical thinkers of the era.

Several interviews are included in the collection. These generally serve to clarify niggling issues that the public fixate upon. Such as, concerns over continuing clashes as negotiations are ongoing, and modes of engagement on the battlefield. Questions like these are never too simple to answer. Why does the New Peoples’ Army continue to use landmines? Why can’t ceasefires be more frequent and longer-lasting? Media will always press for straight, categorical answers, but Prof. Sison’s firm grasp of the core points allows him the leeway to invoke complex contexts even where others see it as deflection.

When asked to address those who may have the barest acquaintance with the Philippine armed conflict in “On the Revolutionary Movement in the Philippines” (2012), Prof. Sison just as well responds succinctly. Asked to sum up the situation in the Philippines, the economy, of the peace talks and of the fighting, he masterfully condenses several volumes of his writings in as little as three paragraphs. The point is, after all, to make people understand better.

And of course, the slightly controversial. In January 2012, he admitted the he is not too optimistic about negotiations under Aquino, which the NDFP had engaged two years prior. In August 2016, he lauded Duterte for the breakthrough in the peace talks, but later reconsidered when relations turn sour and peace consultant Randy Malayao is murdered. Many often deride these efforts as “mistakes” or a waste of time, but Prof. Sison conscientiously refers to the NDFP’s policy of being open to peace negotiations, the “constant policy of seeking a just and lasting peace”. This kind of patience reflects a scrutiny of peace work and experiences in the Philippines, as well as in China, Vietnam, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and South Africa. The dogged insistence on long-term goals rather than short term gains will only ensure that parties no longer return to war after peace agreements.

Many of the concerns are legal. In “Remedies to Obstacles or Problems in the GRP-NDFP Peace Negotiations”, Prof. Sison at the press conference launching the International Legal Advisory Team in 2011 demonstrates his essential understanding of how international laws impact what is, at first glance, a non-international, intra-state conflict. In a simple but studied introduction, Prof. Sison diplomatically emphasizes “political integrity”. In his other articles, however, Prof. Sison refers to the recognition and rights of belligerency as a basis for engagement between the NDFP and the GRP.

Where the status of belligerency is invoked, it triggers international law obligations. In consonance therewith, the NDFP precisely signed on and adheres to international humanitarian law instruments – laws of war – in its conduct, even without reciprocity by the GRP. However, the customary doctrine on belligerency, upon which the NDFP claims rights, has been seen in decline and apparent desuetude after the Second World War. Only a handful of experts have acknowledged otherwise, and as it seems, Prof. Sison could be crucial in convincing more.

His extensive discussion of the profound role of the United States also hints at an extended concept of armed conflict. In a semi-/neo-colonial Philippines, does the involvement of the US on various political aspects internationalize an internal armed conflict? Is there space in law for such “third” category of armed conflict? This also has considerable problem sets for third states and parties who have always found a place in Philippine peace processes. What are the consequence of intervening on either side?

Because the situation is ongoing and the process evolving, there are very few experts and scholars who have dared come forward with conclusive studies and predictions on the Philippine armed conflict, lest they be proven wrong in the long run. As such, it falls upon Prof. Sison to set the tone and substance in the conversation. His evaluation of prospects of the GRP-NDFP peace negotiations at different points in the timeline are always canon and relevant. Obviously, there is no doubt that he is a central figure in the peace negotiations, particularly as there are only a handful of NDFP personalities not working incognito.

Thus, Prof. Sison’s refusal to concede to the lesser “state of insurgency” is expected. To treat the armed conflict as either rebellion, insurgency, or even terrorism has significant personal bearing. Prof. Sison has been labelled a terrorist in different territories, intended to make him pariah and irrelevant. Asked in an interview with the Philippine Daily Inquirer in 2002, how he felt about this, Prof. Sison merely said that he was not intimidated. Given that he still writing to us today tells that he really wasn’t, and that he remains influential – indisputably, and perhaps, irrevocably so. If any, this book is his flex of both the brains and brawn of the Philippine left and proof that Prof. Sison is not a terrorist, but a dyed-in-the-wool revolutionary.

In the latter parts of the book, Prof. Sison mulls over the possibility of him serving in the GRP government, or even being GRP president. “Crooks and butchers have become president in the Philippines,” he says, his attitude starkly more realistic than messianic.

Patience is a virtue, and so is discipline. Prof. Sison shows us the he has both in spades. Decades of exile has not dulled, but instead sharpened his senses for every bit of useful information from and about the Philippines. Writing to Bienvenido Lumbera who turned 80 in 2011, Prof. Sison led the letter from personal reminiscing to a discourse, with every page dripping in the adage: the personal is political. His own 75th birthday wish was a truly proletarian one: To stay healthy and live longer in order to further serve the people.

This book is a political guide and a personal gift from Prof. Sison for all of us interested in peace in the Philippines. In parts where his persona seeps through, it almost feels like a personal conversation. As his words lilt when sharing his life story, we really feel how his heart yearns for mangoes. And as always, for peace.

Thank you, Prof. Sison.