July 6, 2011

Dr. Dante C. Simbulan, Sr.*

*Retired Professor of Political Science and Government

Former Professor, Philippine Military Academy &

University of the Philippines, Ateneo University

Former Dean, College of Arts and Science, Polytechnic University of the Philippines

Political Prisoner of the Marcos Dictatorship

VIEW SLIDE PRESENTATION

INTRODUCTION

From Pax Roman to Pax Americana

In its essence, Imperialism has not really changed through the ages. It has attempted to change its stripes but it has retained its substance. The old Roman Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the Spanish, British, French, and the American Empires have much the same policies, goals, and objectives which are: the policy and practice of extending or expanding its power and dominion over other nations, either by direct conquest and territorial expansion or by more subtle methods and not so subtle methods in order to impose its authority and influence over the captive nations, or both.

This domination extends to all spheres of human activity – it seeks to impose its will on the economic, political, social, and cultural life of the victim nation. Old imperialism does this mainly through the use of force, coercion, and intimidation. Its modern-day practitioners, however, use a combination of methods.

MODERN-DAY IMPERIALISM

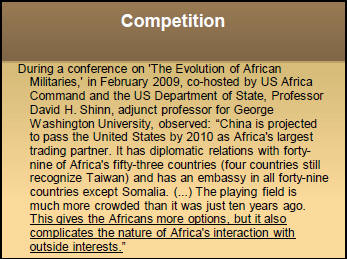

The modern-day imperialists have learned from the bad experiences of old imperialism and have modified and improved their methods. Their methods are largely influenced by the main engine which drives imperialist expansion: Global Capitalism.

Driven by greed for more and more profits, it seeks:

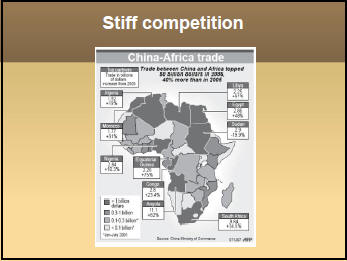

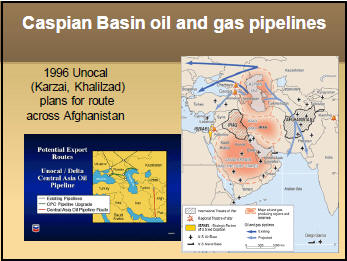

A. The control of territories that are sources of cheap raw materials to feed their hungry factories: oil and gas, iron ore for making steel products, copper, silver, tin, nickel, manganese, etc.;

B. The control of sources of cheap labor mainly from third world countries– former colonies in Asia, Africa and Latin America—as main targets.

C. The control of areas in the world where excess capital can be profitably invested, generating vast wealth and super profits which they bring home to their home countries, while leaving the masses of peoples in the countries they exploit, poor and hungry and their land devastated and robbed of its wealth and resources;

D. The control of profitable markets for their manufactured goods, for business and for trade, usually the densely populated countries of the world with the targeted buying power.

This capitalist engine propels the imperialist country to expand and extend its tentacles all over the globe. Its working slogans are: Free Trade, Globalization, Privatization, Liberalization, Deregulation, etc. It promises “development,” “growth,” and “prosperity.” In practice, however, only the wealthy few they chose to be their junior partners or business agents (compradors) have developed, have grown, and have prospered. In practice, the sharks have taken over and have devoured the weak. The big has eliminated the small. The rich have become richer while the hundreds and hundreds of millions of the world’s poor have become poorer!

Modern-day imperialism uses more subtle and crafty ways to attain its goals. It operates insidiously, always waiting for the opportunity to entrap its victims. It employs deceptive ways of gaining its foreign policy objectives, whether these be economic, political, social, cultural, and military.

The art of deception has been perfected by the practitioners of imperialism. They liberally use euphemisms, that is, the substitution of agreeable inoffensive language for one that more accurately describes reality but which suggests something unpleasant. They use the word “aid,” instead of the more appropriate word “bribe” that better describes the intent of their acts. (I discussed this more fully in “The Art of Keeping Power” in “The Modern Principalia: The Historical Evolution of the Philippine Ruling Oligarchy,” by Dante C. Simbulan, Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Press, 2007, Chapter 5).

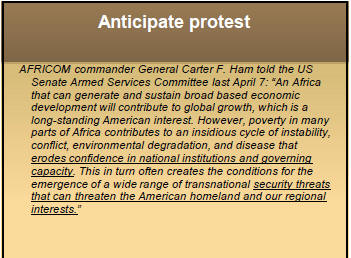

Imperialist forays and military interventions in many parts of the world—in Grenada, Panama, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras, Haiti, the Philippines, Korea, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Lebanon, Somalia and, most recently, in Libya, were explained and “justified” as “peace operations,” operations to save democracy and preserve freedom, or otherwise made for “humanitarian” reasons or concern for human rights.

Modern-day imperialism, therefore, uses many guises, hides behind many masks. It would camouflage or hide its real foreign policy goals and objectives by emphasizing instead its “intention” of spreading democracy, freedom, and human rights throughout the world. The aim is to cloak or to hide its real economic and power goals.

The attainment of these objectives, of course, are extremely detrimental and harmful to the peoples of the captive nations, but they could be very enticing to the native ruling elites who see the prospect of getting more wealthy, thereby increasing their power and dominance over the masses of the people they rule if they join the imperialist bandwagon.

The use of compliant native rulers – the mercenary elites, corrupt oligarchs, military dictators, and just plain undisguised puppets – is another common technique of the imperialist. Their names have changed through time – from the pejorative servants and vassals to rulers of protectorates and client states, to the more appealing “friends and allies,” and “partners in defending democracy and freedom” in the world.

The Strategy and Tactics of US Imperialism under Obama

In May 2010, President Barack Obama outlined a “National Security Strategy” in a White House Proclamation. In this proclamation, he outlined “a strategy for the world we seek” and explicitly stated: “Our national strategy is…. focused on renewing American leadership so that we can more effectively advance our interests in the 21st century. We will do so by building upon the sources of our strength at home while shaping an international order that can meet the challenge of our time.”

His emphasis is on “our multinational engagement with close friends and allies in Europe, Asia, the Americas, and the Middle East – ties which are rooted in shared interests and shared values, and which serve our mutual security and prosperity of the world.”

A lot of these, of course, are clever rhetorical formulations of a wily American president. For the fact remains that US interests are really the interests of the ruling capitalist elites of Wall Street which are closely bound not to the peoples of the world but to the interests of the ruling elites and corrupt oligarchies elsewhere in the world.

Obama also talks of sharing the costs of protecting the world (read: the capitalist global empire) that is, of involvement of regimes which are willing collaborators and accomplices of US imperialism. By assuring the ruling elites of these countries of US protection and “assistance,” the US hopes to entice them to be part of an “alliance” (the so-called “coalition of the willing” in Iraq and Afghanistan are good examples) in defending the empire.

On February 2010, the US Department of Defense issued a Quadrennial Defense Report that outlines the goals and implementation of Obama’s “Top National Priorities”. These are:

A. Prevail in today’s wars (Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Libya, etc.)

B. Prevent and deter conflict by a show of military strength (land, air, and naval forces around the world).

C. Prepare to militarily defend “US national interests”

D. Build the security capacity of partner states (particularly in their counter-insurgency wars)

Defense Secretary Robert Gates states: “Our deterrent remains grounded on land, air, and naval forces (around the world) capable of fighting limited and large-scale conflicts in environments where anti-access weaponry and tactics are used, as well as forces prepared to respond to the full range of challenges posed by state and non-state groups.”

PROTECTING AND DEFENDING THE US EMPIRE

Primary Role of Overseas US Military Bases

At the end of the World War II, the US and its erstwhile “ally” against Hitler, the USSR, parted ways and the “Cold War” between the two superpowers began. The arms race and space race started and the establishment of numerous military bases also followed. In all these activities, both countries invested huge resources.

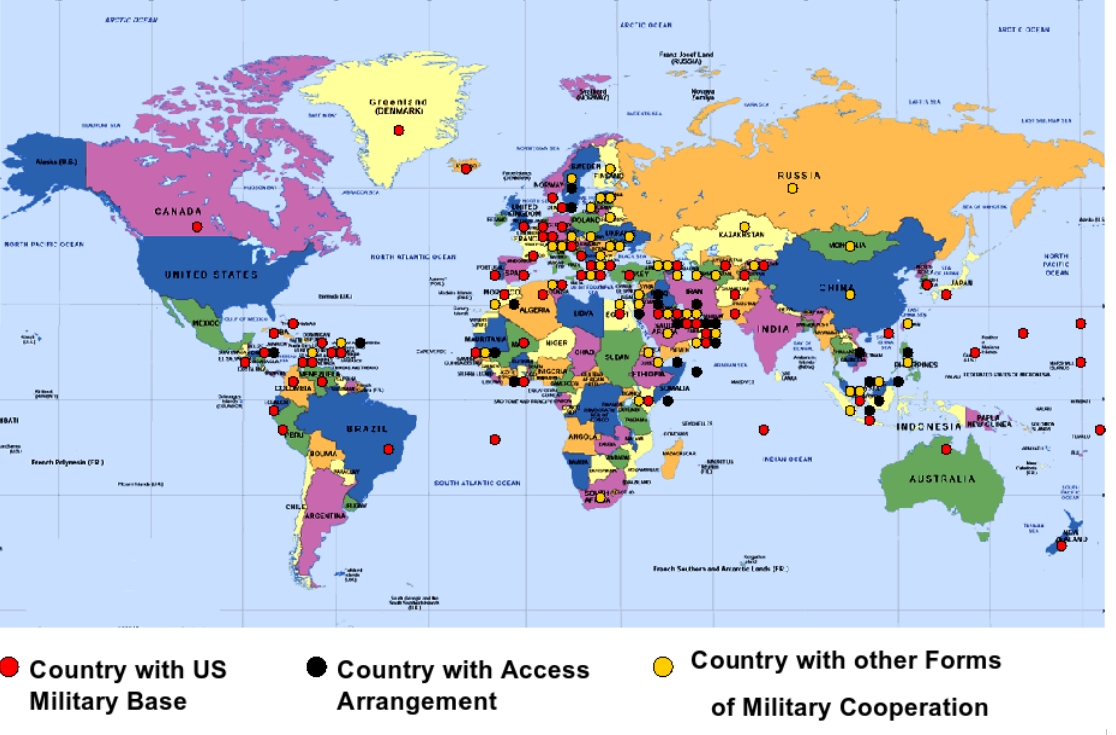

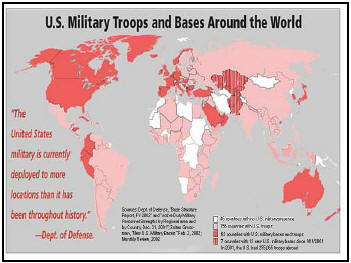

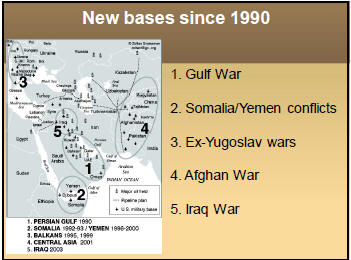

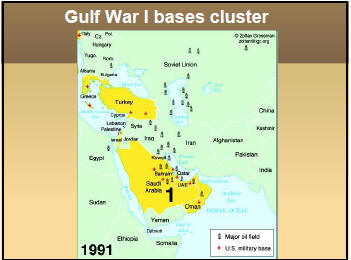

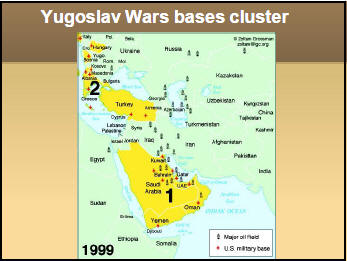

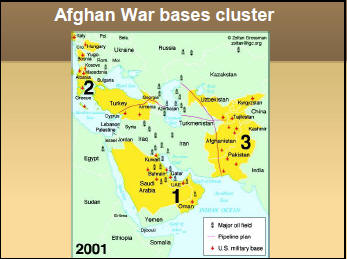

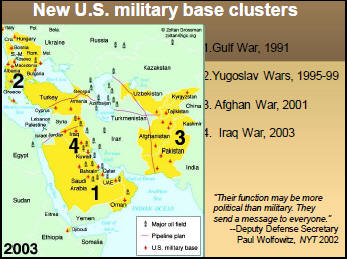

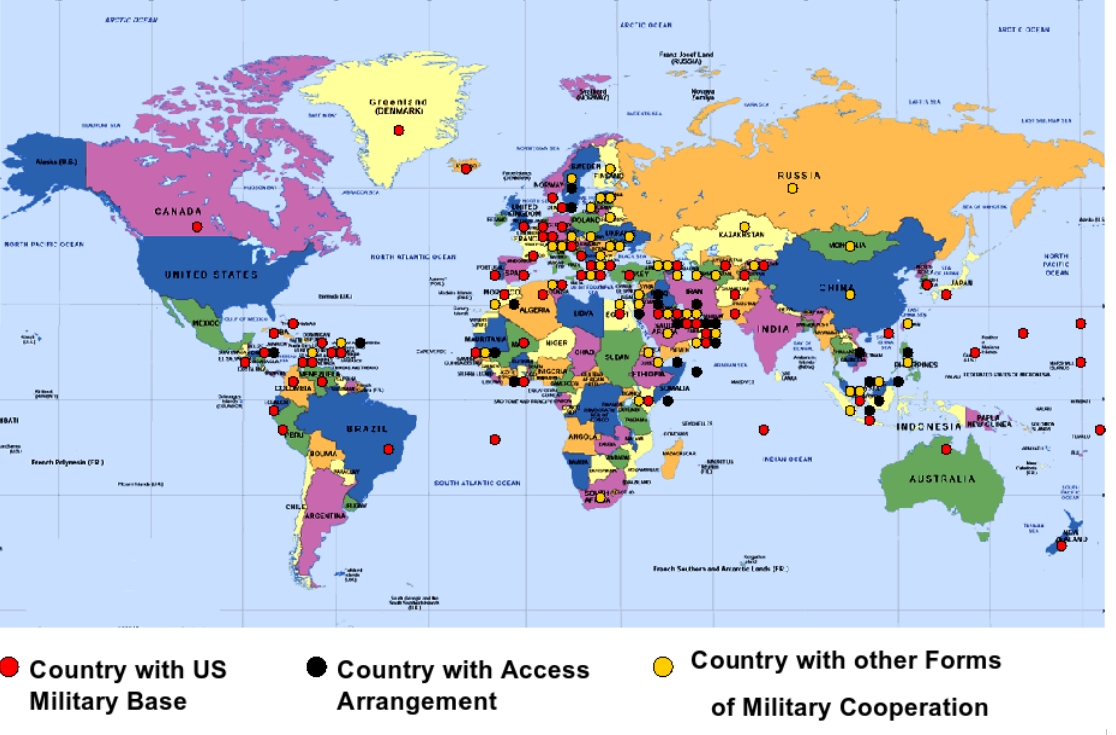

By the end of the Cold War, the US became the lone superpower with the USSR disintegrating to many nation-states. By this time, the US had built on estimated 800 to 1,000 military bases and had stationed hundreds of thousands of US troops around the world.

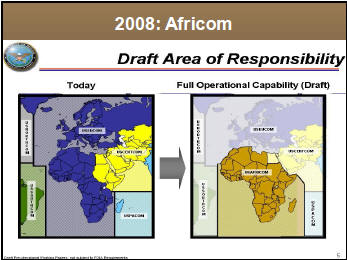

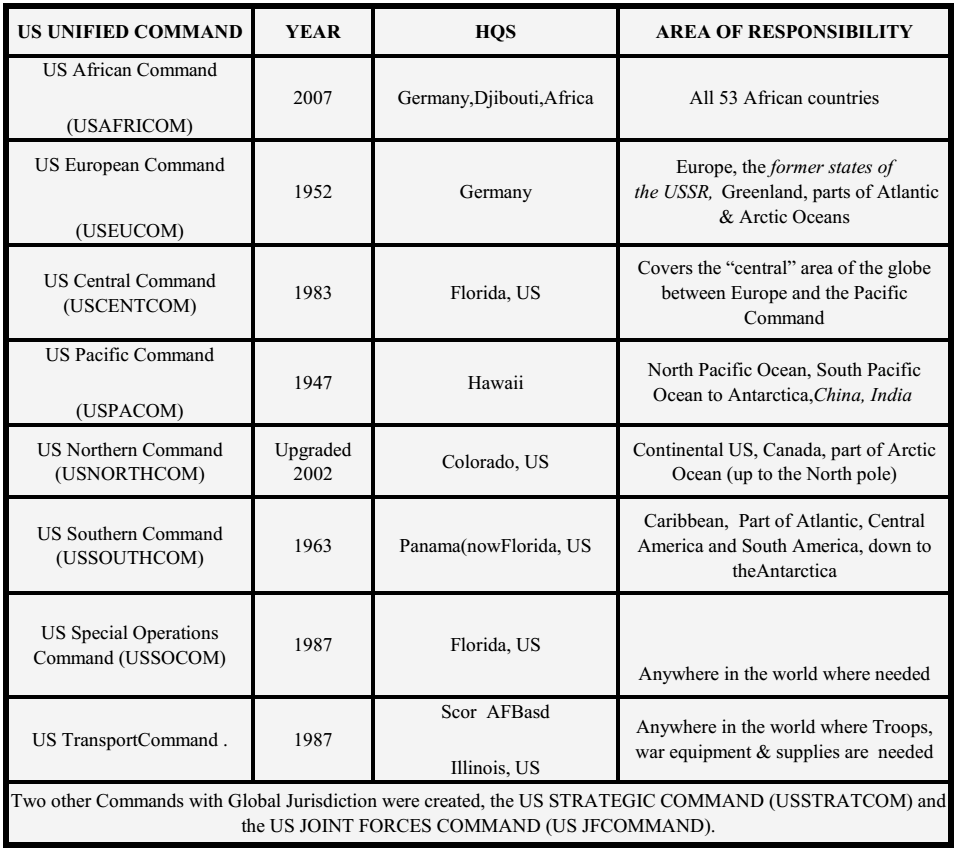

Determined to maintain its superpower status and to protect the vast economic empire it had built, the US proceeded to divide the world into Ten US Global Commands. All the US military bases in the world were placed under these Military Commands.

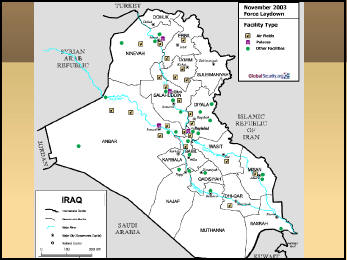

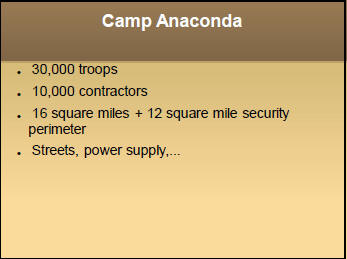

After 9/11, the “Global War on Terror”, Pres. George W. Bush, fuming with anger and outrage at the killing of 3,000 people in the Twin Towers by Al Qaeda operatives unleashed the full might of US military power against Iraq, a country which had nothing to do with 9/11. Bush and his Pentagon minions invented reasons to justify a massive assault on Iraq, falsely claiming that Iraq was a threat to US national security because of its weapons of mass destructions (WMD). Without UN sanction and in violation of international law, the US unilaterally assembled a so-called “coalition of the willing,” bombed and shelled with long-range missiles Baghdad and other cities of Iraq, inflicting thousands of civilian casualties. The invasion of Iraq followed and after defeating a much-inferior and poorly equipped Iraqi army, the US succeeded in its purpose of having a “regime change”. The anti-American Iraqi President, Saddam Hussein and many members of his cabinet were tried, found guilty and hanged by the American-installed Iraqi government.

This invasion of a sovereign and independent country; the destruction of its buildings, road, bridges and infrastructures; and the tortures and killings of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis, many of whom were civilians were all war crimes and crimes against humanity under international law which the imperialist countries are fond of invoking. But the imperial US and its co-conspirators and accomplices who committed all these crimes were not indicated but instead, it was their victims – President Saddam Hussein and members of his cabinet were the ones indicted as war criminals. This is Imperialist Justice. Meanwhile, the BIG OIL companies of the US and its Western accomplices are now in control of Iraqi oil.

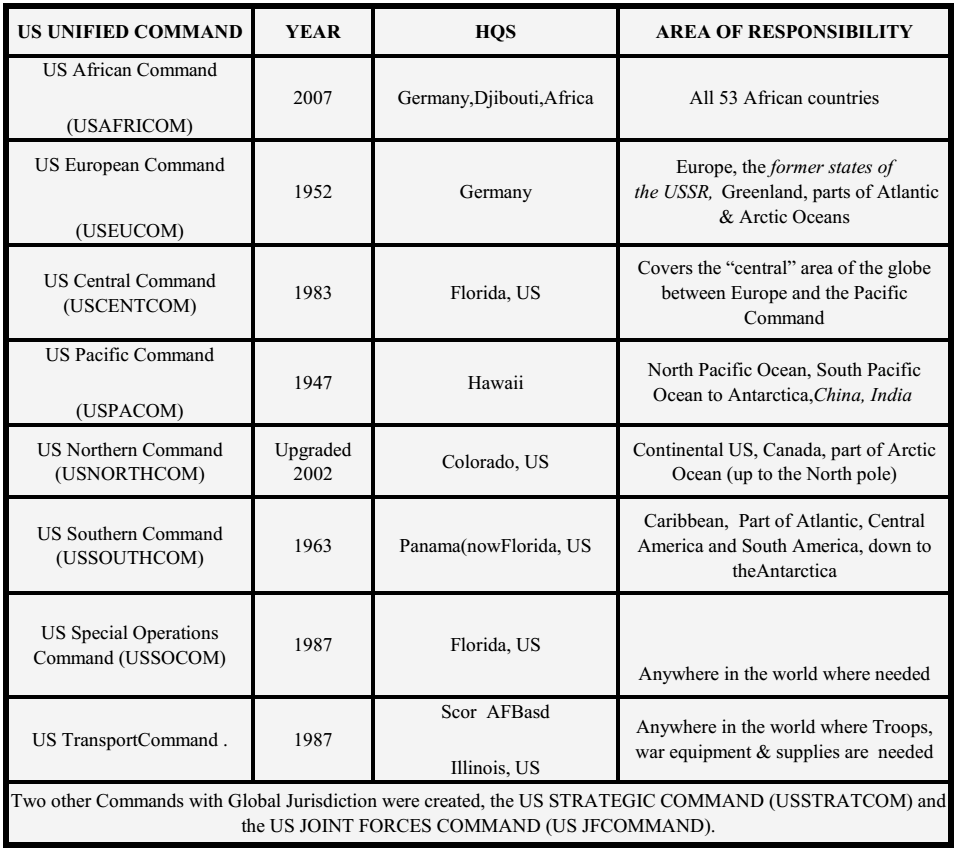

The US Global Military Commands

The table below shows the different US Global Military Commands, their areas of responsibility, the year of their establishment, and the location of their headquarters.

In addition to the above US military global commands, the CIA and the FBI have also been tasked to expand their areas of responsibility. They operate openly or covertly anywhere around the world, often without the knowledge or permission of the country where they operate. The CIA had been operating around the world clandestinely a long time ago. It has its African Division, Far East Division, a Near East Division, a Western Hemisphere Division, A Central American Task Force, Operations Groups in Iraq, Nicaragua, South Asia, etc. (see Secret Wars of the CIA by John Prados, Chicago, 2006).

Even the FBI, which is a domestic investigating agency of the US Justice Department, normally operating in the United States, has now embarked on many overseas operations. It arrests suspected “terrorists” in the territories of supposedly sovereign and independent countries like Pakistan, Yemen, Central and South America and other countries in Africa and in the Middle East. Indeed, both the FBI and the CIA are acting like self-appointed (although illegal) international policemen, exercising police powers in many parts of the world in violation of the independence and sovereign rights of countries, violating principles of international law and the UN Charter, which the US says it subscribes to.

One interesting thing to note is the sheer arrogance of US imperialism in placing the whole world under its US UNIFIED GLOBAL COMMANDS. Even big and powerful countries which are potential adversaries (like Russia and China) were placed under the area of responsibility of these US Military Global Commands. Russia was placed under the responsibility of the US European Command (US EUCOM) and China and India were placed under the US Pacific Command. No other country has done this before, dividing the whole world into actual US Military Commands, each under a four-star general or admiral with the specific mission to protect, defend and enhance US national interests in their respective areas of responsibility. The accusation that the US has appointed itself the “international policeman of the world” is a valid one for it assumes that it can act preemptively and arbitrarily, in violation of international law, in removing or combating what it perceives as “threats to its national security,” particularly in pursuing its so-called “global war on terror.” The only problem is its definitions of “terror” and “terrorist” organizations are rather vague and flexible. It does not apply to the US and its allies and their war crimes and crimes against humanity in their numerous military interventions throughout the world that actually terrorize hundreds of millions of people as acts of terror!

THE DOD BASE STRUCTURE REPORT (September 2008)

This US Defense Department Report outlines the US military installations built around the world.

A second DOD Report released on December 31, 2010 shows the distribution of active duty US military personnel by regions and by country numbering 1,429,367 worldwide: 1,137,716 (in the US and its territories) and 458,500 in foreign countries. This Report also indicate that 101,468 of these are “afloat,” meaning that they are deployed in US Naval Warships operating around the world.

A New Development: A few of the large bases has been reduced but an increasing number of ”Access Arrangements” and other forms of Military Cooperation Agreements have been signed as shown in the map. (countries with Access Arrangements, and Cooperative Security Location.)

THE GLOBAL STRATEGIC STRAITS (CHOKEPOINTS)

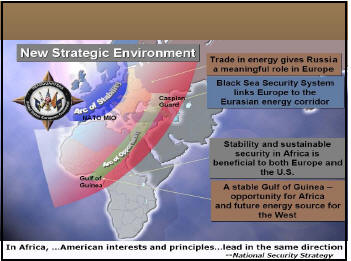

In order to protect and defend US strategic interests and hegemony throughout the world, the US and its allies have established control over strategic straits (chokepoints) around the world.

These chokepoints control the economic lifeblood of the world — the shipping lanes where the commerce and trade of the world and the naval warships that protect such interests and commerce of the major powers pass.

The deployment of overseas US military bases globally is intended, among others, to provide protection and defense of these vital and strategic straits.

The history of how these strategic straits came under the control of the imperial powers is closely linked to the wars and conflict due to the global expansion of the empire-building western powers.

THE STRAIT OF GIBRALTAR

The narrow channel of Gibraltar connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Atlantic Ocean and the countries of Europe. It is also a very important shipping route to the trading countries of Southern Europe and Northern Africa. Through the Suez Canal, these countries are able to trade with Western Asia and beyond. In the past, wars have been fought to control the Strait of Gibraltar.

THE STRAIT OF HORMUZ

Much of the world’s oil coming from the oil-rich region of the Middle East (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Iraq, Iran) pass through the narrow Strait of Ormuz. Iran has a strategic interest in Ormuz because some of the small islands along the strait belong to her. In a future war over oil, Ormuz will certainly be a vital area of contention. The U.S. has permanently stationed naval forces in the area.

SUEZ CANAL

The Suez links the Mediterranean to the Red Sea, thence to the Gulf of Aden and the Horn of Africa. The Suez Canal shortens the shipping lanes from Europe to India and the rest of Asia by over 5,000 miles.

From 1875, the British Empire controlled the Canal. In 1922, the British granted a fake independence to Egypt which continued to be ruled by corrupt monarchs who were British proxies. The British retain effective control of Egypt, particularly the Suez Canal where they maintained military and naval bases and garrisons. It was only when Col. Abdel Nasser, an Arab nationalist leader who overthrew the British puppet, Egyptian King Farouk, when the British were forced to give up control of the Canal in 1956. When Nasser nationalized the canal, the US proxy in the Middle East, Israel, invaded Egypt while the British and the French sent their armed forces to retake the Canal. Suez was reopened in l957. The Suez Canal was closed again during the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. It was not reopened until 1975.

STRAIT OF MALACCA

The Strait connects the Indian Ocean (and beyond) with the South China Sea and the Pacific. Bordering Sumatra (Indonesia), Thailand and the Malay Coast, it is the shortest trade route between India and China. The Strait of Malacca is one of the most heavily travelled channels in the world. In the past, it came successively under the control of the Arabs, the Portuguese, the Dutch (who colonized Indonesia) and the British (who colonized Malaya and Singapore). Today giant oil tankers from the Middle East transport oil to China, Korea, Japan and other countries of South East Asia and East Asia. Shipping pass through the Spratleys whose ownership is now the bone of contention between the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan and China. The US is (again) trying to insert itself into the conflict.

PANAMA CANAL

The Panama Canal links the East Coast of the US, the Atlantic and the Caribbean

to the Pacific and Asia. Panama used to be part of Colombia. When the US saw the great potential of linking the Atlantic with the Pacific Ocean and Asia through a canal, it encouraged and aided a local rebellion against Colombia. The rebels, with US support won the Panama section, and declared independence from Colombia in 1903. The US immediately recognized the new country of Panama and took control of the Canal Zone. Under a treaty, the Canal reverted back to Panama but the Canal is still virtually under US protection and control.

HORN OF AFRICA

Traditionally, the “Horn of Africa” refers to the region consisting of Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Somalia. After 9-11, the US took interest in the region by virtue of its strategic location. Yemen, the country where Osama bin Laden was born and where Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula is based became a country of interest to the US. So is Somalia where a strong anti-US Islamic movement was in .power.

The US wanted a base in the Horn of Africa from which it could launch wars of intervention in the region. Through dollar diplomacy and the promise of continuing aid, the US persuaded the Djibouti government to lease around 57 acres in Djibouti. In 2006, an access agreement was made and the lease of land was increased to 500 acres. The lease agreement was for 5 years but it can be renewed.

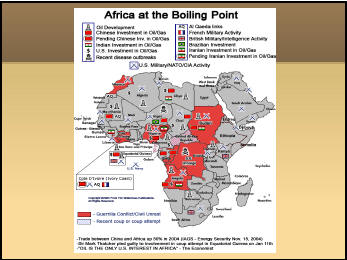

The US Africa Command can now launch COIN operations in the rest of Africa with the Djibouti base at Camp Lemonnier as the logistics and launching area.

In 2006, the US Africa Command was able to persuade the Ethiopian government to invade Somalia. The US provided money, weapons and munitions, military advisers to the invading Ethiopia army. The Somalian government was toppled and the President was replaced by one more acceptable to the US.

CONCLUSION

In protecting and defending the global interests of the US, Barack Obama and his strategic

planners in the Pentagon and the State Department have shifted from the unilateral and arrogant “cowboy” approach of Pres. GW BUSH to a multilateral policy in which it tries to involve fellow imperialist powers before launching its defense of the Empire and its wars of aggression.

The US is now experimenting with a new form of warfare involving the collaboration of (1) Special Forces and (2) the CIA’s paramilitary units of its “Special Activities Division’ and (3) other units of the US Armed Forces. The Pentagon’s Joint Special Operations Command (part of SOCOM) runs the show. This new form of warfare is now being tested in Yemen, Afghanistan and Pakistan and in training sites in Fort Bragg, North Carolina (Home 0f Special Forces ) and in Fort Benning, Georgia ( Home of the Rangers).

The assassination of Osama Bin Laden in Pakistan is a result of such new method of the US Special Operations Command. It was an operation participated in by the CIA (use of Pakistani “assets,” intel-gathering Drones, the US Navy warship and the aircraft carrier-based SEALs who executed the final assault. It was an operation which took months (maybe years) in the making.

This new form of warfare is complemented by the COIN shift from a purely conventional approach (the use of conventional forces) to the application of “Soft Power” (e.g. psychological and asymmetrical warfare). Initiated by Sec. Donald Rumsfeld and tried in several countries of Africa it has been expanded by Sec. Robert Gates and it is now being used in many countries faced with “insurgency” problems (read: revolutionary movements) . (See 2009 US Counter Insurgency Guide; In the Philippines we now have OPLAN ”Bayanihan” being implemented by the Armed Forces of the Philippines)

Except for the major Headquarters located in continental US and abroad, the US is experimenting more and more on the use of ACCESS agreements (SOFA, MLSA, VFA, etc.), stationing smaller, housekeeping forces and highly trained Special Operations Forces to wage “asymmetrical” or “irregular warfare” against any non-state forces that are hostile to the interests of US Imperialism and its local ruling partners. Targeted enemies include revolutionary forces fighting for national and social liberation, which are first demonized and tagged as “terrorist” organizations to justify their “legitimate” inclusion against the US global war on terror.

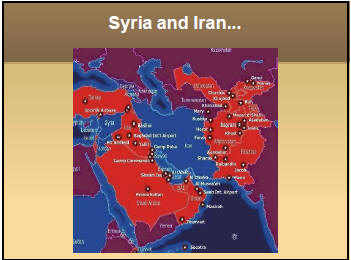

In the “US Global War on Terror,” US military forces are authorized by their superiors (civilian and military) to violate international law, the territorial integrity of independent and sovereign states (e.g. Pakistan, Somalia, the Philippines); conduct preemptive strikes, decapitate (assassinate) a country’s political leadership, effect regime change, torture or kill civilian suspects, etc. (Examples abound: Haiti, Honduras, Grenada, Panama, Somalia, Iraq and Afghanistan; there are ongoing attempts in Libya and Syria by US and NATO (and most probably Israel’s notorious MOSSAD). Obviously these are all indictable war crimes but the International Criminal Court and the UN Security Council, strongly influenced and manipulated by the US and NATO, are turning a blind eye, pretending not to notice these gross violations of international law and crimes against humanity, or are just looking the other way!!

Barack Obama differs from George W. Bush only on the emphasis in the use of “soft power” rather than the use of brute military force. But Obama’s way, while more subtle and deceptive, also aims to protect the so-called “strategic interests” of US Imperialism.

The peoples of the world must unite as one and resist these criminal violations of international law and the territorial integrity of sovereign and independent states by US Imperialism.

There is an urgent need for the world’s peoples to unite in solidarity and wage a global struggle to eliminate all US military bases in the world; unite and struggle against all forms of intervention by US IMPERIALISM and its collaborators! Let us all join hands and struggle for Peace with Justice throughout the world!

REFERENCES

DOCUMENTS AND ARTICLES

Strategic Sea Trade Routes

Noer, John H. & Gregory, David. Chokepoints: Maritime Economic Concerns in Southeast Asia. (1996). Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf&AD=ADA319445

Panama Canal. (2011). In Answers.com. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.answers.com/topic/canal-zone

Strait of Gibraltar. (2011). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/233262/Strait-of-Gibraltar

Strait of Hormuz. (2011). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/271900/Strait-of-Hormuz

Strait of Malacca. (2011). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/359411/Strait-of-Malacca

Suez Canal. (2011). In Answers.com. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.answers.com/topic/suez-canal

US Unified Command Plan

About United States Africa Command. (2011). U.S. Africa Command. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.africom.mil/AfricomFAQs.asp

Area of Responsibility. (2011). United States Southern Command. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.southcom.mil/AppsSC/pages/aoi.php

Command History Overview. (2011). United States Southern Command. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.southcom.mil/AppsSC/factFiles.php?id=76

Countries in USPACOM Area of Responsibility (AOR). United States Pacific Command. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.pacom.mil/web/site_pages/uspacom/regional%20map.shtm

United States European Command: A Brief History. (n.d.). United States European Command. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.eucom.mil/english/history.asp

U.S. Central Command History. (n.d.). United States Central Command. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.centcom.mil/en/about-centcom/our-history/

U.S. Northern Command History. (n.d.) United States Northern Command. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.northcom.mil/About/history_education/history.html

USPACOM History. (n.d.) United States Pacific Command. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.pacom.mil/web/site_pages/uspacom/history.shtml

USTRANSCOM History. (n.d.) United States Transportation Command. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from www.transcom.mil/about/summary.cfm

Deployment of US Special Operations Forces Abroad

Davies, Lynn & Shapiro, Jeremy (eds.). (2003). The U.S. Army and the New National Security Strategy. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/2010/MR1657.pdf

Department of Defense. (2010). Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country (309A), December 31, 2010. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/2010/hst1003.pdf

Department of Defense. (2009). Base Structure Report Fiscal Year 2009Baseline. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.defense.gov/pubs/pdfs/2009baseline.pdf

Department of Defense, United States of America. (2010). Quadrennial Defense Review Report. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.defense.gov/qdr/qdr%20as%20of%2029jan10%201600.PDF

Eland, Ivan and Rudy, John. (2002). Special Operations Military Training Abroad and Its Dangers. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.bulatlat.com/news/2-5/2-5-reader-cato.html

Feickert, Andrew & Livinsgton, Thomas. (2011). U.S. Special Operations Forces (SOF): Background and Issues for Congress. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS21048.pdf

Gates, Robert. (2009). A Balanced Strategy: Reprogramming the Pentagon for a New Age. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/63717/robert-m-gates/a-balanced-strategy

Klare, Michael & Kornbluh Peter. (1988). The New Interventionism: Low Intensity Warfare in the 1980s and Beyond. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.thirdworldtraveler.com/US_ThirdWorld/Low_Intensity_Warfare.html

Priest, Dana. (1998). U.S. Military Trains Foreign Troops. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/overseas/overseas1a.htm

Taillon, J. Paul. (2007). Coalition Special Operation Forces: Building Partner Capacity. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.journal.dnd.ca/vo8/no3/doc/taillon-eng.pdf

Zeigler, Jack Jr. (2003). The Army Special Operations Forces Role in Force Projection. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.fas.org/man/eprint/zeigler.pdf

Types of US Bases Abroad

Dufour, Jules. (2011). The Worldwide Network of US Militaty Bases: The Global Deployment of US Military Personnel. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=5564

Simbulan, Roland. (2010). The Pentagon’s Secret War and the Facilities in the Philippines. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.arkibongbayan.org/2011/2011-02Feb06-FilAmWar/doc2/CPER_SIMBULAN.pdf

US Counterinsurgency Strategy Worldwide

Asian Defense News. (2010). Philippines to Adopt US Strategy in Counter-insurgency Starting January 1. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://revolutionaryfrontlines.wordpress.com/2010/12/21/philippines-to-adopt-us-strategy-in-counter-insurgency-starting/

Headquarters, US Department of the Army. (2008). Army Special Operations Forces Unconventional Warfare. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://file.wikileaks.info/leak/us-fm3-05-130.pdf

Headquarters, US Department of the Army. (1994). Foreign Internal Defense, Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Special Forces. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.wikileaks.ch/wiki/US_Special_Forces_Foreign_Internal_Defense_Tactics_Techniques_and_Procedures_for Special_Forces,_FM_31.20-3,_2003

Headquarters, US Department of the Army. (2003). Special Forces Unconventional Warfare Operations. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://file.wikileaks.info/leak/us-fm3-05-130.pdf

Headquarters, US Department of the Army (Gen. David Petraeus?). (2009). The US Counterinsurgency Field Manual(FM3-24.2). Retrieved June 27, 2011 from http://www.fas.org/irp/doddir/army/fmi3-24-2.pdf

Metz, Steven. (2007). Learning from Iraq. Counterinsurgency in American Strategy. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pdffiles/pub752.pdf

Oliveros, Benjie. (2006). Political Killings, Part of U.S.-Phil. Counterinsurgency Strategies. Retrieved June 16, 2011 from http://www.bulatlat.com/news/6-46/6-46-us3.htm

US Department of Defense. (2009). The 2009 US Counterinsurgency Guide. Retrieved June 15, 2011 from http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/119629.pdf

Office of the President, The White House, Washington, D.C. (2010). The United States National Security Strategy

(May 2010). Retrieved June15, 2011 from

http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/rss_viewer/national_security_strategy.pdf

(ILPS), call on the entire ILPS, its global region region committees, its national chapters and member-organizations to undertake all possible and necessary actions against the US plan to bomb Syria and engage in a brazen war of aggression against Syria and the Syrian people.

(ILPS), call on the entire ILPS, its global region region committees, its national chapters and member-organizations to undertake all possible and necessary actions against the US plan to bomb Syria and engage in a brazen war of aggression against Syria and the Syrian people.